30. Symmetric Multiprocessing (SMP)#

30.1. Introduction#

RTEMS Symmetric Multiprocessing (SMP) support is available on a subset of target architectures supported by RTEMS. Further on some target architectures, it is only available on a subset of BSPs. The user is advised to check the BSP specific documentation and RTEMS source code to verify the status of SMP support for a specific BSP. The following architectures have support for SMP:

AArch64,

ARMv7-A,

i386,

PowerPC,

RISC-V, and

SPARC.

Warning

SMP support is only available if RTEMS was built with the SMP build configuration option enabled.

RTEMS is supposed to be a real-time operating system. What does this mean in the context of SMP? The RTEMS interpretation of real-time on SMP is the support for Clustered Scheduling with priority based schedulers and adequate locking protocols. One aim is to enable a schedulability analysis under the sporadic task model [Bra11] [BW13].

30.2. Background#

30.2.1. Application Configuration#

By default, the maximum processor count is set to one in the application configuration. To enable SMP, the application configuration option CONFIGURE_MAXIMUM_PROCESSORS must be defined to a value greater than one. It is recommended to use the smallest value suitable for the application in order to save memory. Each processor needs an idle thread and interrupt stack for example.

The default scheduler for SMP applications supports up to 32 processors and is a global fixed priority scheduler, see also Clustered Scheduler Configuration.

The following compile-time test can be used to check if the SMP support is available or not.

#include <rtems.h>

#ifdef RTEMS_SMP

#warning "SMP support is enabled"

#else

#warning "SMP support is disabled"

#endif

30.2.2. Examples#

For example applications see testsuites/smptests.

30.2.3. Uniprocessor versus SMP Parallelism#

Uniprocessor systems have long been used in embedded systems. In this hardware model, there are some system execution characteristics which have long been taken for granted:

one task executes at a time

hardware events result in interrupts

There is no true parallelism. Even when interrupts appear to occur at the same time, they are processed in largely a serial fashion. This is true even when the interupt service routines are allowed to nest. From a tasking viewpoint, it is the responsibility of the real-time operatimg system to simulate parallelism by switching between tasks. These task switches occur in response to hardware interrupt events and explicit application events such as blocking for a resource or delaying.

With symmetric multiprocessing, the presence of multiple processors allows for true concurrency and provides for cost-effective performance improvements. Uniprocessors tend to increase performance by increasing clock speed and complexity. This tends to lead to hot, power hungry microprocessors which are poorly suited for many embedded applications.

The true concurrency is in sharp contrast to the single task and interrupt model of uniprocessor systems. This results in a fundamental change to uniprocessor system characteristics listed above. Developers are faced with a different set of characteristics which, in turn, break some existing assumptions and result in new challenges. In an SMP system with N processors, these are the new execution characteristics.

N tasks execute in parallel

hardware events result in interrupts

There is true parallelism with a task executing on each processor and the possibility of interrupts occurring on each processor. Thus in contrast to their being one task and one interrupt to consider on a uniprocessor, there are N tasks and potentially N simultaneous interrupts to consider on an SMP system.

This increase in hardware complexity and presence of true parallelism results in the application developer needing to be even more cautious about mutual exclusion and shared data access than in a uniprocessor embedded system. Race conditions that never or rarely happened when an application executed on a uniprocessor system, become much more likely due to multiple threads executing in parallel. On a uniprocessor system, these race conditions would only happen when a task switch occurred at just the wrong moment. Now there are N-1 tasks executing in parallel all the time and this results in many more opportunities for small windows in critical sections to be hit.

30.2.4. Task Affinity#

RTEMS provides services to manipulate the affinity of a task. Affinity is used to specify the subset of processors in an SMP system on which a particular task can execute.

By default, tasks have an affinity which allows them to execute on any available processor.

Task affinity is a possible feature to be supported by SMP-aware schedulers. However, only a subset of the available schedulers support affinity. Although the behavior is scheduler specific, if the scheduler does not support affinity, it is likely to ignore all attempts to set affinity.

The scheduler with support for arbitary processor affinities uses a proof of concept implementation. See https://gitlab.rtems.org/rtems/programs/gsoc/-/issues/34

30.2.5. Task Migration#

With more than one processor in the system tasks can migrate from one processor to another. There are four reasons why tasks migrate in RTEMS.

The scheduler changes explicitly via rtems_task_set_scheduler() or similar directives.

The task processor affinity changes explicitly via rtems_task_set_affinity() or similar directives.

The task resumes execution after a blocking operation. On a priority based scheduler it will evict the lowest priority task currently assigned to a processor in the processor set managed by the scheduler instance.

The task moves temporarily to another scheduler instance due to locking protocols like the Multiprocessor Resource Sharing Protocol (MrsP) or the O(m) Independence-Preserving Protocol (OMIP).

Task migration should be avoided so that the working set of a task can stay on the most local cache level.

30.2.6. Clustered Scheduling#

The scheduler is responsible to assign processors to some of the threads which are ready to execute. Trouble starts if more ready threads than processors exist at the same time. There are various rules how the processor assignment can be performed attempting to fulfill additional constraints or yield some overall system properties. As a matter of fact it is impossible to meet all requirements at the same time. The way a scheduler works distinguishes real-time operating systems from general purpose operating systems.

We have clustered scheduling in case the set of processors of a system is partitioned into non-empty pairwise-disjoint subsets of processors. These subsets are called clusters. Clusters with a cardinality of one are partitions. Each cluster is owned by exactly one scheduler instance. In case the cluster size equals the processor count, it is called global scheduling.

Modern SMP systems have multi-layer caches. An operating system which neglects cache constraints in the scheduler will not yield good performance. Real-time operating systems usually provide priority (fixed or job-level) based schedulers so that each of the highest priority threads is assigned to a processor. Priority based schedulers have difficulties in providing cache locality for threads and may suffer from excessive thread migrations [Bra11] [CMV14]. Schedulers that use local run queues and some sort of load-balancing to improve the cache utilization may not fulfill global constraints [GCB13] and are more difficult to implement than one would normally expect [LLF+16].

Clustered scheduling was implemented for RTEMS SMP to best use the cache topology of a system and to keep the worst-case latencies under control. The low-level SMP locks use FIFO ordering. So, the worst-case run-time of operations increases with each processor involved. The scheduler configuration is quite flexible and done at link-time, see Clustered Scheduler Configuration. It is possible to re-assign processors to schedulers during run-time via rtems_scheduler_add_processor() and rtems_scheduler_remove_processor(). The schedulers are implemented in an object-oriented fashion.

The problem is to provide synchronization primitives for inter-cluster synchronization (more than one cluster is involved in the synchronization process). In RTEMS there are currently some means available

events,

message queues,

mutexes using the O(m) Independence-Preserving Protocol (OMIP),

mutexes using the Multiprocessor Resource Sharing Protocol (MrsP), and

binary and counting semaphores.

The clustered scheduling approach enables separation of functions with real-time requirements and functions that profit from fairness and high throughput provided the scheduler instances are fully decoupled and adequate inter-cluster synchronization primitives are used.

To set the scheduler of a task see rtems_scheduler_ident() and rtems_task_set_scheduler().

30.2.7. OpenMP#

OpenMP support for RTEMS is available via the GCC provided libgomp. There is libgomp support for RTEMS in the POSIX configuration of libgomp since GCC 4.9 (requires a Newlib snapshot after 2015-03-12). In GCC 6.1 or later (requires a Newlib snapshot after 2015-07-30 for <sys/lock.h> provided self-contained synchronization objects) there is a specialized libgomp configuration for RTEMS which offers a significantly better performance compared to the POSIX configuration of libgomp. In addition application configurable thread pools for each scheduler instance are available in GCC 6.1 or later.

The run-time configuration of libgomp is done via environment variables documented in the libgomp manual. The environment variables are evaluated in a constructor function which executes in the context of the first initialization task before the actual initialization task function is called (just like a global C++ constructor). To set application specific values, a higher priority constructor function must be used to set up the environment variables.

#include <stdlib.h>

void __attribute__((constructor(1000))) config_libgomp( void )

{

setenv( "OMP_DISPLAY_ENV", "VERBOSE", 1 );

setenv( "GOMP_SPINCOUNT", "30000", 1 );

setenv( "GOMP_RTEMS_THREAD_POOLS", "1$2@SCHD", 1 );

}

The environment variable GOMP_RTEMS_THREAD_POOLS is RTEMS-specific. It

determines the thread pools for each scheduler instance. The format for

GOMP_RTEMS_THREAD_POOLS is a list of optional

<thread-pool-count>[$<priority>]@<scheduler-name> configurations separated

by : where:

<thread-pool-count>is the thread pool count for this scheduler instance.$<priority>is an optional priority for the worker threads of a thread pool according topthread_setschedparam. In case a priority value is omitted, then a worker thread will inherit the priority of the OpenMP master thread that created it. The priority of the worker thread is not changed by libgomp after creation, even if a new OpenMP master thread using the worker has a different priority.@<scheduler-name>is the scheduler instance name according to the RTEMS application configuration.

In case no thread pool configuration is specified for a scheduler instance,

then each OpenMP master thread of this scheduler instance will use its own

dynamically allocated thread pool. To limit the worker thread count of the

thread pools, each OpenMP master thread must call omp_set_num_threads.

Lets suppose we have three scheduler instances IO, WRK0, and WRK1

with GOMP_RTEMS_THREAD_POOLS set to "1@WRK0:3$4@WRK1". Then there are

no thread pool restrictions for scheduler instance IO. In the scheduler

instance WRK0 there is one thread pool available. Since no priority is

specified for this scheduler instance, the worker thread inherits the priority

of the OpenMP master thread that created it. In the scheduler instance

WRK1 there are three thread pools available and their worker threads run at

priority four.

30.2.8. Atomic Operations#

There is no public RTEMS API for atomic operations. It is recommended to use the standard C <stdatomic.h> or C++ <atomic> APIs in applications.

30.3. Application Issues#

Most operating system services provided by the uniprocessor RTEMS are available in SMP configurations as well. However, applications designed for an uniprocessor environment may need some changes to correctly run in an SMP configuration.

As discussed earlier, SMP systems have opportunities for true parallelism which was not possible on uniprocessor systems. Consequently, multiple techniques that provided adequate critical sections on uniprocessor systems are unsafe on SMP systems. In this section, some of these unsafe techniques will be discussed.

In general, applications must use proper operating system provided mutual exclusion mechanisms to ensure correct behavior.

30.3.1. Task variables#

Task variables are ordinary global variables with a dedicated value for each thread. During a context switch from the executing thread to the heir thread, the value of each task variable is saved to the thread control block of the executing thread and restored from the thread control block of the heir thread. This is inherently broken if more than one executing thread exists. Alternatives to task variables are POSIX keys and TLS. All use cases of task variables in the RTEMS code base were replaced with alternatives. The task variable API has been removed in RTEMS 5.1.

30.3.2. Highest Priority Thread Never Walks Alone#

On a uniprocessor system, it is safe to assume that when the highest priority task in an application executes, it will execute without being preempted until it voluntarily blocks. Interrupts may occur while it is executing, but there will be no context switch to another task unless the highest priority task voluntarily initiates it.

Given the assumption that no other tasks will have their execution interleaved with the highest priority task, it is possible for this task to be constructed such that it does not need to acquire a mutex for protected access to shared data.

In an SMP system, it cannot be assumed there will never be a single task executing. It should be assumed that every processor is executing another application task. Further, those tasks will be ones which would not have been executed in a uniprocessor configuration and should be assumed to have data synchronization conflicts with what was formerly the highest priority task which executed without conflict.

30.3.3. Disabling of Thread Preemption#

A thread which disables preemption prevents that a higher priority thread gets hold of its processor involuntarily. In uniprocessor configurations, this can be used to ensure mutual exclusion at thread level. In SMP configurations, however, more than one executing thread may exist. Thus, it is impossible to ensure mutual exclusion using this mechanism. In order to prevent that applications using preemption for this purpose, would show inappropriate behaviour, this feature is disabled in SMP configurations and its use would case run-time errors.

30.3.4. Disabling of Interrupts#

A low overhead means that ensures mutual exclusion in uniprocessor configurations is the disabling of interrupts around a critical section. This is commonly used in device driver code. In SMP configurations, however, disabling the interrupts on one processor has no effect on other processors. So, this is insufficient to ensure system-wide mutual exclusion. The macros

rtems_interrupt_disable(),

rtems_interrupt_enable(), and

rtems_interrupt_flash().

are disabled in SMP configurations and its use will cause compile-time warnings and link-time errors. In the unlikely case that interrupts must be disabled on the current processor, the

rtems_interrupt_local_disable(), and

rtems_interrupt_local_enable().

macros are now available in all configurations.

Since disabling of interrupts is insufficient to ensure system-wide mutual exclusion on SMP a new low-level synchronization primitive was added – interrupt locks. The interrupt locks are a simple API layer on top of the SMP locks used for low-level synchronization in the operating system core. Currently, they are implemented as a ticket lock. In uniprocessor configurations, they degenerate to simple interrupt disable/enable sequences by means of the C pre-processor. It is disallowed to acquire a single interrupt lock in a nested way. This will result in an infinite loop with interrupts disabled. While converting legacy code to interrupt locks, care must be taken to avoid this situation to happen.

1#include <rtems.h>

2

3void legacy_code_with_interrupt_disable_enable( void )

4{

5 rtems_interrupt_level level;

6

7 rtems_interrupt_disable( level );

8 /* Critical section */

9 rtems_interrupt_enable( level );

10}

11

12RTEMS_INTERRUPT_LOCK_DEFINE( static, lock, "Name" )

13

14void smp_ready_code_with_interrupt_lock( void )

15{

16 rtems_interrupt_lock_context lock_context;

17

18 rtems_interrupt_lock_acquire( &lock, &lock_context );

19 /* Critical section */

20 rtems_interrupt_lock_release( &lock, &lock_context );

21}

An alternative to the RTEMS-specific interrupt locks are POSIX spinlocks. The

pthread_spinlock_t is defined as a self-contained object, e.g. the

user must provide the storage for this synchronization object.

1#include <assert.h>

2#include <pthread.h>

3

4pthread_spinlock_t lock;

5

6void smp_ready_code_with_posix_spinlock( void )

7{

8 int error;

9

10 error = pthread_spin_lock( &lock );

11 assert( error == 0 );

12 /* Critical section */

13 error = pthread_spin_unlock( &lock );

14 assert( error == 0 );

15}

In contrast to POSIX spinlock implementation on Linux or FreeBSD, it is not

allowed to call blocking operating system services inside the critical section.

A recursive lock attempt is a severe usage error resulting in an infinite loop

with interrupts disabled. Nesting of different locks is allowed. The user

must ensure that no deadlock can occur. As a non-portable feature the locks

are zero-initialized, e.g. statically initialized global locks reside in the

.bss section and there is no need to call pthread_spin_init().

30.3.5. Interrupt Service Routines Execute in Parallel With Threads#

On a machine with more than one processor, interrupt service routines (this includes timer service routines installed via rtems_timer_fire_after()) and threads can execute in parallel. Interrupt service routines must take this into account and use proper locking mechanisms to protect critical sections from interference by threads (interrupt locks or POSIX spinlocks). This likely requires code modifications in legacy device drivers.

30.3.6. Timers Do Not Stop Immediately#

Timer service routines run in the context of the clock interrupt. On uniprocessor configurations, it is sufficient to disable interrupts and remove a timer from the set of active timers to stop it. In SMP configurations, however, the timer service routine may already run and wait on an SMP lock owned by the thread which is about to stop the timer. This opens the door to subtle synchronization issues. During destruction of objects, special care must be taken to ensure that timer service routines cannot access (partly or fully) destroyed objects.

30.3.7. False Sharing of Cache Lines Due to Objects Table#

The Classic API and most POSIX API objects are indirectly accessed via an object identifier. The user-level functions validate the object identifier and map it to the actual object structure which resides in a global objects table for each object class. So, unrelated objects are packed together in a table. This may result in false sharing of cache lines. The effect of false sharing of cache lines can be observed with the TMFINE 1 test program on a suitable platform, e.g. QorIQ T4240. High-performance SMP applications need full control of the object storage [Dre07]. Therefore, self-contained synchronization objects are now available for RTEMS.

30.4. Implementation Details#

This section covers some implementation details of the RTEMS SMP support.

30.4.1. Low-Level Synchronization#

All low-level synchronization primitives are implemented using C11 atomic operations, so no target-specific hand-written assembler code is necessary. Four synchronization primitives are currently available

ticket locks (mutual exclusion),

MCS locks (mutual exclusion),

barriers, implemented as a sense barrier, and

sequence locks [Boe12].

A vital requirement for low-level mutual exclusion is FIFO fairness since we are interested in a predictable system and not maximum throughput. With this requirement, there are only few options to resolve this problem. For reasons of simplicity, the ticket lock algorithm was chosen to implement the SMP locks. However, the API is capable to support MCS locks, which may be interesting in the future for systems with a processor count in the range of 32 or more, e.g. NUMA, many-core systems.

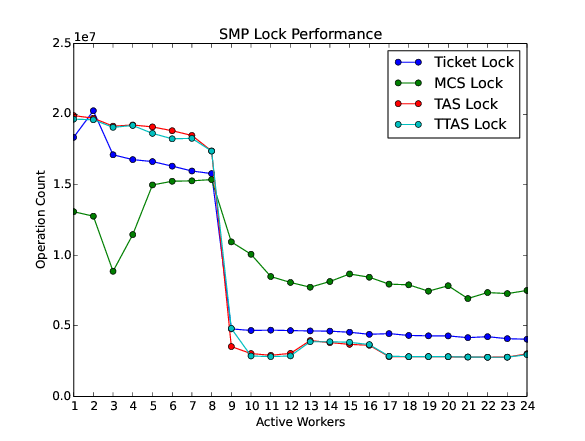

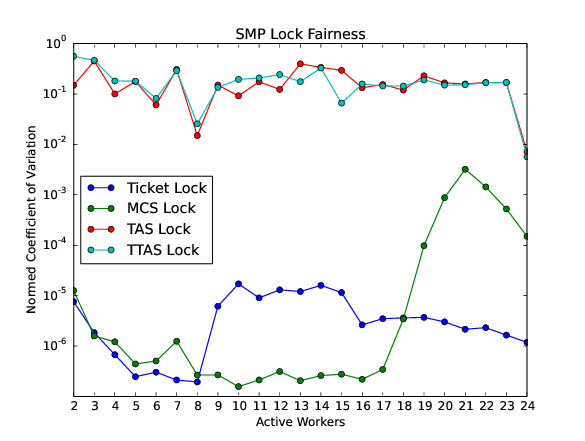

The test program SMPLOCK 1 can be used to gather performance and fairness data for several scenarios. The SMP lock performance and fairness measured on the QorIQ T4240 follows as an example. This chip contains three L2 caches. Each L2 cache is shared by eight processors.

30.4.2. Internal Locking#

In SMP configurations, the operating system uses non-recursive SMP locks for low-level mutual exclusion. The locking domains are roughly

a particular data structure,

the thread queue operations,

the thread state changes, and

the scheduler operations.

For a good average-case performance it is vital that every high-level synchronization object, e.g. mutex, has its own SMP lock. In the average-case, only this SMP lock should be involved to carry out a specific operation, e.g. obtain/release a mutex. In general, the high-level synchronization objects have a thread queue embedded and use its SMP lock.

In case a thread must block on a thread queue, then things get complicated. The executing thread first acquires the SMP lock of the thread queue and then figures out that it needs to block. The procedure to block the thread on this particular thread queue involves state changes of the thread itself and for this thread-specific SMP locks must be used.

In order to determine if a thread is blocked on a thread queue or not thread-specific SMP locks must be used. A thread priority change must propagate this to the thread queue (possibly recursively). Care must be taken to not have a lock order reversal between thread queue and thread-specific SMP locks.

Each scheduler instance has its own SMP lock. For the scheduler helping protocol multiple scheduler instances may be in charge of a thread. It is not possible to acquire two scheduler instance SMP locks at the same time, otherwise deadlocks would happen. A thread-specific SMP lock is used to synchronize the thread data shared by different scheduler instances.

The thread state SMP lock protects various things, e.g. the thread state, join operations, signals, post-switch actions, the home scheduler instance, etc.

30.4.3. Profiling#

To identify the bottlenecks in the system, support for profiling of low-level synchronization is optionally available. The profiling support is an RTEMS build time configuration option and is implemented with an acceptable overhead, even for production systems. A low-overhead counter for short time intervals must be provided by the hardware.

Profiling reports are generated in XML for most test programs of the RTEMS testsuite (more than 500 test programs). This gives a good sample set for statistics. For example the maximum thread dispatch disable time, the maximum interrupt latency or lock contention can be determined.

<ProfilingReport name="SMPMIGRATION 1">

<PerCPUProfilingReport processorIndex="0">

<MaxThreadDispatchDisabledTime unit="ns">36636</MaxThreadDispatchDisabledTime>

<MeanThreadDispatchDisabledTime unit="ns">5065</MeanThreadDispatchDisabledTime>

<TotalThreadDispatchDisabledTime unit="ns">3846635988

</TotalThreadDispatchDisabledTime>

<ThreadDispatchDisabledCount>759395</ThreadDispatchDisabledCount>

<MaxInterruptDelay unit="ns">8772</MaxInterruptDelay>

<MaxInterruptTime unit="ns">13668</MaxInterruptTime>

<MeanInterruptTime unit="ns">6221</MeanInterruptTime>

<TotalInterruptTime unit="ns">6757072</TotalInterruptTime>

<InterruptCount>1086</InterruptCount>

</PerCPUProfilingReport>

<PerCPUProfilingReport processorIndex="1">

<MaxThreadDispatchDisabledTime unit="ns">39408</MaxThreadDispatchDisabledTime>

<MeanThreadDispatchDisabledTime unit="ns">5060</MeanThreadDispatchDisabledTime>

<TotalThreadDispatchDisabledTime unit="ns">3842749508

</TotalThreadDispatchDisabledTime>

<ThreadDispatchDisabledCount>759391</ThreadDispatchDisabledCount>

<MaxInterruptDelay unit="ns">8412</MaxInterruptDelay>

<MaxInterruptTime unit="ns">15868</MaxInterruptTime>

<MeanInterruptTime unit="ns">3525</MeanInterruptTime>

<TotalInterruptTime unit="ns">3814476</TotalInterruptTime>

<InterruptCount>1082</InterruptCount>

</PerCPUProfilingReport>

<!-- more reports omitted --->

<SMPLockProfilingReport name="Scheduler">

<MaxAcquireTime unit="ns">7092</MaxAcquireTime>

<MaxSectionTime unit="ns">10984</MaxSectionTime>

<MeanAcquireTime unit="ns">2320</MeanAcquireTime>

<MeanSectionTime unit="ns">199</MeanSectionTime>

<TotalAcquireTime unit="ns">3523939244</TotalAcquireTime>

<TotalSectionTime unit="ns">302545596</TotalSectionTime>

<UsageCount>1518758</UsageCount>

<ContentionCount initialQueueLength="0">759399</ContentionCount>

<ContentionCount initialQueueLength="1">759359</ContentionCount>

<ContentionCount initialQueueLength="2">0</ContentionCount>

<ContentionCount initialQueueLength="3">0</ContentionCount>

</SMPLockProfilingReport>

</ProfilingReport>

30.4.4. Scheduler Helping Protocol#

The scheduler provides a helping protocol to support locking protocols like the O(m) Independence-Preserving Protocol (OMIP) or the Multiprocessor Resource Sharing Protocol (MrsP). Each thread has a scheduler node for each scheduler instance in the system which are located in its TCB. A thread has exactly one home scheduler instance which is set during thread creation. The home scheduler instance can be changed with rtems_task_set_scheduler(). Due to the locking protocols a thread may gain access to scheduler nodes of other scheduler instances. This allows the thread to temporarily migrate to another scheduler instance in case of preemption.

The scheduler infrastructure is based on an object-oriented design. The scheduler operations for a thread are defined as virtual functions. For the scheduler helping protocol the following operations must be implemented by an SMP-aware scheduler

ask a scheduler node for help,

reconsider the help request of a scheduler node,

withdraw a schedule node.

All currently available SMP-aware schedulers use a framework which is customized via inline functions. This eases the implementation of scheduler variants. Up to now, only priority-based schedulers are implemented.

In case a thread is allowed to use more than one scheduler node it will ask these nodes for help

in case of preemption, or

an unblock did not schedule the thread, or

a yield was successful.

The actual ask for help scheduler operations are carried out as a side-effect of the thread dispatch procedure. Once a need for help is recognized, a help request is registered in one of the processors related to the thread and a thread dispatch is issued. This indirection leads to a better decoupling of scheduler instances. Unrelated processors are not burdened with extra work for threads which participate in resource sharing. Each ask for help operation indicates if it could help or not. The procedure stops after the first successful ask for help. Unsuccessful ask for help operations will register this need in the scheduler context.

After a thread dispatch the reconsider help request operation is used to clean up stale help registrations in the scheduler contexts.

The withdraw operation takes away scheduler nodes once the thread is no longer allowed to use them, e.g. it released a mutex. The availability of scheduler nodes for a thread is controlled by the thread queues.

30.4.5. Thread Dispatch Details#

This section gives background information to developers interested in the interrupt latencies introduced by thread dispatching. A thread dispatch consists of all work which must be done to stop the currently executing thread on a processor and hand over this processor to an heir thread.

In SMP systems, scheduling decisions on one processor must be propagated to other processors through inter-processor interrupts. A thread dispatch which must be carried out on another processor does not happen instantaneously. Thus, several thread dispatch requests might be in the air and it is possible that some of them may be out of date before the corresponding processor has time to deal with them. The thread dispatch mechanism uses three per-processor variables,

the executing thread,

the heir thread, and

a boolean flag indicating if a thread dispatch is necessary or not.

Updates of the heir thread are done via a normal store operation. The thread dispatch necessary indicator of another processor is set as a side-effect of an inter-processor interrupt. So, this change notification works without the use of locks. The thread context is protected by a TTAS lock embedded in the context to ensure that it is used on at most one processor at a time. Normally, only thread-specific or per-processor locks are used during a thread dispatch. This implementation turned out to be quite efficient and no lock contention was observed in the testsuite. The heavy-weight thread dispatch sequence is only entered in case the thread dispatch indicator is set.

The context-switch is performed with interrupts enabled. During the transition from the executing to the heir thread neither the stack of the executing nor the heir thread must be used during interrupt processing. For this purpose a temporary per-processor stack is set up which may be used by the interrupt prologue before the stack is switched to the interrupt stack.

30.4.6. Per-Processor Data#

RTEMS provides two means for per-processor data:

Per-processor data which is used by RTEMS itself is contained in the Per_CPU_Control structure. The application configuration via <rtems/confdefs.h> creates a table of these structures (_Per_CPU_Information[]). The table is dimensioned according to the count of configured processors (CONFIGURE_MAXIMUM_PROCESSORS).

For low level support libraries an API for statically allocated per-processor data is available via <rtems/score/percpudata.h>. This API is not intended for general application use. Please ask on the development mailing list in case you want to use it.

30.4.7. Thread Pinning#

Thread pinning ensures that a thread is only dispatched to the processor on which it is pinned. It may be used to access per-processor data structures in critical sections with enabled thread dispatching, e.g. a pinned thread is allowed to block. The _Thread_Pin() operation will pin the executing thread to its current processor. A thread may be pinned recursively, the last unpin request via _Thread_Unpin() revokes the pinning.

Thread pinning should be used only for short critical sections and not all the time. Thread pinning is a very low overhead operation in case the thread is not preempted during the pinning. A preemption will result in scheduler operations to ensure that the thread executes only on its pinned processor. Thread pinning must be used with care, since it prevents help through the locking protocols. This makes the OMIP and MrsP locking protocols ineffective if pinned threads are involved.

The thread pinning is not intended for general application use. Please ask on the development mailing list in case you want to use it.